Interview with Cindy, Darrell, and Betsy May, 2025

NO ALTERATION

11.21.25

Hayner Public Library in Alton, IL

Conversation with Danya Gerasimova

Edited by Danya Gerasimova

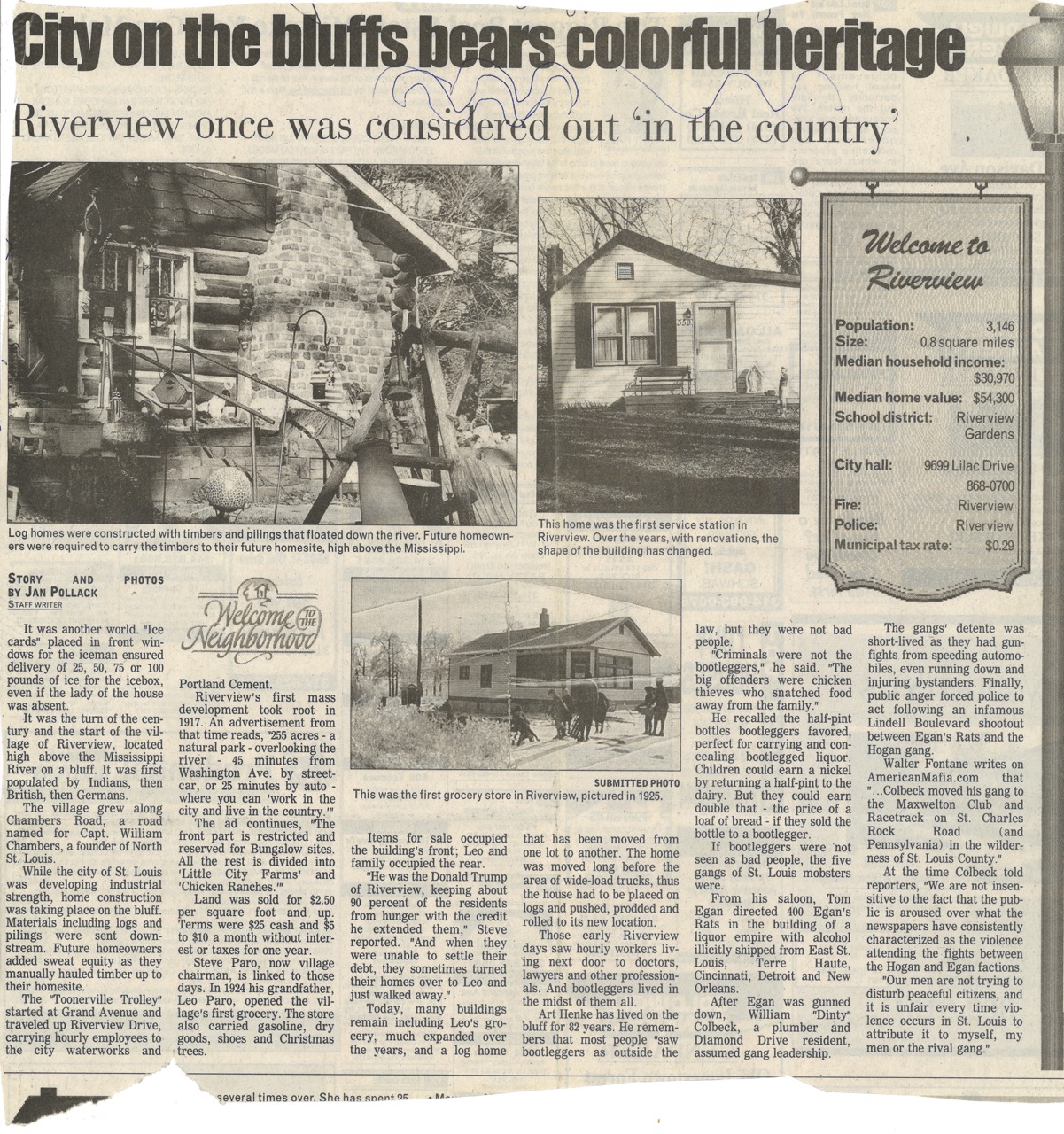

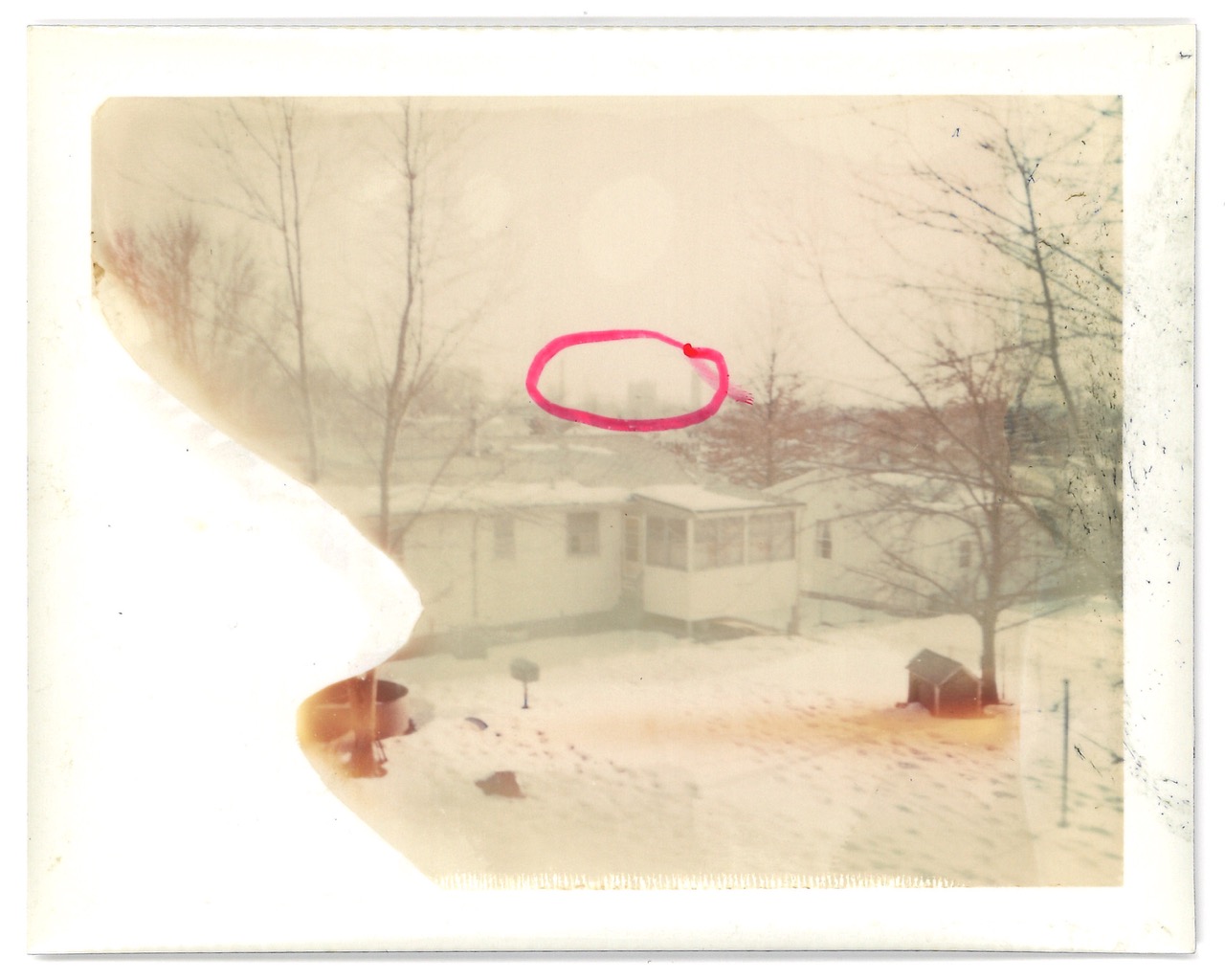

Cindy and Darrell May moved to Bellefontaine Neighbors near the Missouri Portland Cement factory with their daughter Betsy in 1967. Cindy May took part in the campaign against the factory's pollution and has kept an archive of documents pertaining to the campaign.

Danya Gerasimova:

When did you move to Bellefontaine Neighbors?

Cindy May:

We moved there in 1967 and lived there for 35 years. When we moved in, Betsy was about two and a half. It was a good neighborhood then. The neighbors were all wonderful. By the time we moved out of there, we had keys to five of the neighbors' houses. We all took care of each other.

Betsy May:

We were the second owners of the house that we moved into, but everybody else who lived around us was the original owner, and their children were older. We were the young family on the street.

Cindy May:

They were all Catholic, so they all had five or six kids a piece. The U-Haul pulled up in front of our house, and all of the neighborhood kids came up there, sat on the curb, and watched everything come off the truck.

Danya Gerasimova:

Where did you guys move from and why?

Cindy May:

We lived in an apartment building in Jennings.

Darrell May:

And we moved to Jennings from Alton, Illinois, because we both worked in North St. Louis County.

Danya Gerasimova:

Where did you work at the time?

Cindy May:

I worked at a Top Value Stamps store at the River Roads Mall.

Darrell May:

I worked at the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. You've never heard of them, but have you ever heard of Boeing? It's all the same place. I worked there for 40 years. I worked on the assembly line.

Danya Gerasimova:

Why did you choose to move to Bellefontaine Neighbors from Jennings?

Darrell May:

Well, we were looking to buy a home, and that's where we happened to find one. That's the only reason.

Danya Gerasimova:

How would you describe the neighborhood at the time?

Darrell May:

The Bellefontaine area was built after World War II, and there were pretty large subdivisions built. Our house was built in 1955. Almost all of the residents were people who had come back from the war, got married, looked for housing, and that's what was there. Much of North County had farming communities until soldiers came back from World War II. That's when they built North County. If you start looking at those houses, they're all very similar. They were all built at the same time by a couple of big contractors. Somebody made a lot of money.

Cindy May:

All the houses in Bellefontaine Neighbors had asbestos shingles, and every house was white. The only differences between the houses were different color shutters.

Darrell May:

Most of the families had been there for at least 10 years before we got there, and they stayed there until they either died or moved away because they got too old to stay. Which is sort of what we did, but we were about 10 years behind them.

The neighborhood of Bellefontaine Neighbors between Chambers Rd and Highway 67 is called Bissell Hills. General Daniel Bissell's Home is out there, and that's how it got its name. Our neighborhood, Little Bissell Hills, was east of there next to Riverview, on the far side of the railroad track. We were kind of the outcasts of Bissell Hills.

Danya Gerasimova:

What did some of your neighbors do for work?

Darrell May:

They worked at different factories around there. We had two different neighbors who worked for the Terminal Railroad, which was a good job. A neighbor across the street worked at Procter & Gamble down on Hall Street. Rich worked for the Telephone Company. Just working class people. They worked wherever they'd gotten a job and made enough money to make a house payment. But I didn't know anybody who worked at the Missouri Portland Cement plant.

Danya Gerasimova:

What did folks do in their free time?

Betsy May:

We went to Surrey Lane [Athletic Fields]. The kids played Khoury League soccer, baseball, and softball. Then the Bellefontaine Recreational Center was built on Bellefontaine Road, and we spent a lot of time there.

Dad played softball with work. Mom did mother's circle and PTA type stuff. Once in a while when Dad would get paid on Friday, we'd go to McDonald's, and he'd give me five dollars to pay for five meals for five people. Later on, we would go to Cusumano's in Glasgow Village and have pizza there. That was when we were older kids though.

Cindy May:

We would go to the River Dairy Thrift Market grocery store.

Betsy May:

It was originally at Toelle Ln and Chambers Rd, and then it moved up to Chambers Rd and Bellefontaine Rd.

I was also in Girl Scouts for a short period of time. My two younger brothers were in Scouts for a lot longer than I was.

Cindy May:

And they made Eagle Scout, both of them. We spent about 25 years in Scouting: Brownies, Girl Scouts, Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts. I used to run the Christmas Tree Lot for the Boy Scouts.

Betsy May:

That was at Friedens Chapel.

Darrell May:

That's also right on the corner of Bellefontaine Rd and Chambers Rd.

Cindy May:

We had a key to it for like 15–20 years. We didn't belong to the church, but we were accepted into the church because of the Scouts.

Danya Gerasimova:

Was it a majority white neighborhood at the time?

Darrell May:

Almost entirely.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you remember any Black families in the area in the '60s and '70s at all?

Betsy May:

In the '70s, there was a family that moved in. But they were on Chambers Road down by Northgate. There were two homes up there, and those were the first Black kids in the school. But before that, I don't think there were any people of color in the whole area.

Darrell May:

I worked with a guy named John Gasway. He was Black and considerably older than me. I told him where I lived, and he said when he was a kid, he lived down there on Leeton. He hunted rabbits up where our subdivision was built later, because it was just a brushy field. John was around 40 when I was 20. So that would have been before or during World War II.

Danya Gerasimova:

When did you first become aware of the Missouri Portland Cement factory?

Darrell May:

It was not long after we moved there. We knew it was there when we moved, but we didn't know anything about it. We became aware of how it affected us in the fall. You would get a heavy dew on your car, and when the factory would blow the ash out, it would settle on your car. Then the sun would come out and bake that water off, and it would leave this layer on the car... I'm not saying it was cement, and I'm not saying it was acid—I think it was a combination of both. It would etch into the paint surface of your automobile, and you couldn't clean it off.

Cindy May:

You would start rubbing it off with your hands, and your fingers would be bleeding. It was pretty tough.

Darrell May:

You noticed it the most on the weekends. We were told that they'd get high pressure air hoses and clean the smoke stack. There's a big chimney down there, and I guess the ash from the cement kiln went up and accumulated there. They didn't want it in there, so they’d blow it out at night and on the weekends. And when it blew our way, it would settle on everybody's houses. The gutters weighed 10 pounds a foot from that stuff settling for years and years. But where you really noticed it was on your car.

I'm sure the ash was coming out all the time in operation, but it would come out probably a hundred times more when they were cleaning. Did it get worse after we moved there too?

Cindy May:

It did.

Darrell May:

Or did we just notice it more when we bought the new car? I'm not sure. But it was just generally known throughout the neighborhood. Everybody had the same problem.

Danya Gerasimova:

What else do you remember about the factory and quarry throughout the first few years? Did you pass by them much?

Darrell May:

We would drive by, but it was just there. It was still operating pretty well. They'd quarry the material out of the quarry and drive it across the road in big trucks. So you had to be aware that those trucks were going to be passing by.

Betsy May:

We didn't have central air in the house when we moved in there. So at night, when it was warm outside, we'd open the windows. And when the windows were open, you could hear the machinery down there squeaking all night long. You could hear it all the way up to our house.

Cindy May:

There was a piece of property adjacent to the quarry. There were a lot of arrowheads and things found there.

Betsy May:

On the backside of the quarry. People would go up there after it would rain. I heard kids talking about finding things like that up there.

Darrell May:

Yes. It's used as a landfill now.

Danya Gerasimova:

Did you ever play at the factory or the quarry as a kid, Betsy?

Betsy May:

No, I never went down that way.

Cindy May:

After the factory had already closed, our son would go down there.

Darrell May:

I don't think anybody went down there to play while it was in operation because it ran all the time. It was a 24 hour operation.

Cindy May:

There were a couple of families that lived across the road, so they probably were the ones that went down and played there. Their names were the Mesners and the Understalls. Our son went to school with those two.

Darrell May:

They lived in that little one street community that's sort of still there.

Betsy May:

One of my classmates, Donna Brickey, lived in one of those houses across from the factory with her grandmother, but she recently passed away during COVID. I don't know if she had any siblings.

Danya Gerasimova:

Did members of their families work at the factory?

Betsy May:

I think there was a kid in my class whose dad worked there. He would have been born around 1964. I remember him saying something to me about being mad that somebody lost their job when the plant shut down.

Danya Gerasimova:

How did the neighborhood organizing against the cement factory pollution get started?

Cindy May:

I got out there, went from neighbor to neighbor, and talked to them. We wrote letters and sent out pamphlets.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you remember how that began?

Betsy May:

Maybe with that lady named Irma that lived on the corner of Science Hill Dr and Scenic Dr?

Danya Gerasimova:

Irma Bosley?

Cindy May:

Yes! Very nice lady. She was much involved in going after the cement plant long before I was. They lived on the corner of Science Hill Dr and Scenic Dr. Their house backed up to the houses in Riverview.

Betsy May:

Her husband too. They were both active, I think.

Danya Gerasimova:

So did Irma Bosley approach you?

Cindy May:

I probably approached her. I think when I was collecting money for the Cancer Society, she was one of my ladies that collected in that area.

The Cancer Society would call me up and say, "Hey, will you go out and canvas the neighborhood and collect money for us?" I'd put the money in an envelope and turn it in to a volunteer in a higher position. Then they would turn it in to the central people, and eventually the Cancer Society got the money.

Darrell May:

She was involved right at the street level.

Danya Gerasimova:

Were you doing this on top of work?

Cindy May:

I didn't work by then.

Betsy May:

By then, she was a stay at home mom, because there were already two of us.

Cindy May:

So this would have been in 1969–1970.

Danya Gerasimova:

So you stopped working around then and began volunteering with the Cancer Society?

Cindy May:

Yes.

Danya Gerasimova:

Did you meet a lot of the neighbors going door to door?

Cindy May:

Yes.

Danya Gerasimova:

How else did you meet with other women in the neighborhood? Were there meetings or town halls of some sort for residents concerned with cement dust?

Cindy May:

Driveways. Kids.

Darrell May:

That's just where everybody met. You get four or five women out there at the end of somebody's driveway—they chatter all day.

Betsy May:

It was informal. They were getting together and talking about how it was affecting them. And she met other women through the kids, because she was a young mom, and everybody else had kids who were teenagers and even adults. So when one of us would get sick, she would talk to one of the neighbors. "Can you look at this rash?" Things like that. That was the first stop before we ever went to the doctor, “What does the neighbor think?”

Cindy May:

That's true, yes. I would say, "Help me. I don't know what to do." And they were all good neighbors. Very good neighbors.

Darrell May:

Our driveway was more popular. All these houses in the neighborhood were built about the same, but we had our garage converted into an additional bedroom and had a new garage built with a new driveway. So we had a double driveway. We were one of the only ones in the neighborhood with that big of a driveway. And that was a playground for the kids a lot of the time. Kids would just show up.

Cindy May:

They would just gravitate to it.

Betsy May:

Back then, you were just kind of loose in the neighborhood.

Darrell May:

Do you know what a Big Wheel is? A tricycle made of plastic. They were very popular in the ‘70s. I don't know how many Big Wheels got their front wheel completely ground off going round and round in our driveway, because it was twice the size of any other patch of concrete in the whole community.

Danya Gerasimova:

Were you ever a member of the Bellefontaine Neighbors citizen group ABCD, Against Breathing Cement Dust?

Cindy May:

I might remember something about that, but I don't know if I was actually a member of that group.

Darrell May:

I don't remember any of that. She did all of this. I was off at work all the time.

Cindy May:

I would write letters to the County Health Department. Roos was the County Supervisor. I invited him to park his car on my street for a week.

Darrell May:

I don't think he took her up.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you remember interacting with Donald Pecsok, head of the County air pollution control office?

Cindy May:

He never showed up. We did have somebody from the St. Louis County Health Department come out and put in a collection device in our backyard. It collected the dust in tupperware dishes. Then they would come out, pick it up, take it back, and check it.

Darrell May:

This device they put in our backyard sat on a pole. Basically, it was an all metal container. Did they plug it into our electricity?

Cindy May:

Yes. We paid for the electricity.

Darrell May:

It had a windvane on it. And on the collection bucket, it had a lid, which was electrically connected to the windvane. That thing stayed closed until the wind was blowing from the direction of the cement company, and then the lid would come open. When the wind changed, it closed again. So supposedly, it was only open when the debris was flowing in our direction. And it was on there for what, a couple of months?

Cindy May:

Yes.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you remember what year this was?

Cindy May:

1972.

Darrell May:

We were the only ones in the neighborhood that had something like that put in the yard, as far as I know. And why they chose our backyard, I don't know either. [To Cindy, laughing:] Probably because you were squawking.

Danya Gerasimova:

And how did the results come out?

Darrell May:

I don't know.

Cindy May:

It just kind of went away.

Darrell May:

If we got a report, it was written in a way that we didn't understand anyways. Parts per million and this and that. Unless you've got some background in that, that really doesn't mean a whole lot.

Danya Gerasimova:

Did the County take any action after monitoring these emissions in 1972?

Darrell May:

I don't know if they ever took any actions that meant anything. That’s just my opinion. I don't have privy to all the real information, but I think when they finally closed the cement plant, it was because it was so old and unprofitable. It wasn't worth putting the money in to operate it. From the pollution compliance standpoint, it probably would have cost more to keep it going than it was worth. I think it would have cost more to meet the new standards that were being created than to build a new plant somewhere else. And I think that quarry next door was running out of material.

Danya Gerasimova:

This 1974 news clipping [from Cindy’s folder of archived documents] talks about the residents of Bellefontaine Neighbors considering filing a class action lawsuit against the cement company. Were you part of a class action lawsuit?

Darrell May:

I don't remember that.

Cindy May:

I don't remember it either.

Danya Gerasimova:

I want to ask you about a few people linked to the campaign against the Missouri Portland Cement factory whose names appear in documents archived by the State Historical Society. Do you remember Alderman Bob Doerr?

Darrell May:

Yes, absolutely. Bob was at the house a few times.

Danya Gerasimova:

Have you talked to him much about the factory?

Cindy May:

I don't know if he was much involved in it. He was aware of it.

Darrell May:

I think he probably did what he could. I don't know how aggressive he was about it.

Danya Gerasimova:

Have you come in contact with the League of Women Voters of Metropolitan St. Louis and Esther Clark?

Cindy May:

No.

Danya Gerasimova:

How about John Warnock?

Cindy May:

No.

Danya Gerasimova:

What about Rose Levering? She would've probably been young in the mid ‘70s, a recent graduate from UMSL. It seems like she conducted a study about pollution in Bellefontaine Neighbors.

Cindy May:

No.

Betsy May:

Do you remember any formal study being done once the factory closed?

Cindy May:

No.

Betsy May:

Yeah, mom talked to people and she had the equipment put in the yard, but I don't think anybody came back and tied everything up in a neat little bow and said, "Here's the impact you had."

Danya Gerasimova:

Were you aware of any other cases of folks organizing similarly to how you did?

Cindy May:

There was a neighborhood on the other side of the cement plant, and I think they were probably doing something too. But we never got together on that.

Danya Gerasimova:

In Baden?

Betsy May:

No. It was across from Bob Russell Park, in the area of St. Cyr Rd and Bellefontaine Rd.

Cindy May:

It was right on the other side of the [Maline] Creek.

Betsy May:

It was still part of Bellefontaine Neighbors, but it was just a different neighborhood. I do have a friend that lived over there. Her name is Patty Hawkins.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you remember if pollution from the cement factory was getting any better in the late '70s?

Darrell May:

It seemed like for the last few years before they shut down, it just got worse and worse.

Danya Gerasimova:

In 1977, the County did adapt stricter pollution regulations as a result of organizing by Bellefontaine Neighbors residents. They created new regulations affecting not only the Missouri Portland Cement factory but also a lot of other industrial facilities in North County. Do you remember any talk of that in 1977?

Darrell May:

I don't remember.

Danya Gerasimova:

Cindy, were you still involved with the campaign efforts by then? Or only in the early '70s?

Cindy May:

I was mostly involved in the early '70s.

Betsy May:

I think once the plant shut down and we didn't have the ash on our cars anymore, that’s when we were like, "Well, it's over."

Danya Gerasimova:

The plant was shut down in '81. Do you remember finding out about it? And what sort of reactions did folks in the neighborhood have?

Darrell May:

I don't remember.

Betsy May:

It was just done.

Darrell May:

That was one issue we didn’t have to deal with any longer. [To Betsy:] But you were saying somebody you went to school with was not happy?

Betsy May:

Yes, it affected somebody in his family who worked there.

But it seems to me like the dust wasn't as big of a problem closer to when they shut down though. Maybe the amount of dust decreased before '81, or maybe they weren't manufacturing as much. Am I wrong?

Cindy May:

I don't think they were manufacturing as much, if I can remember.

Betsy May:

I might be wrong about that. But it seemed like after a while, it just wasn't a topic for discussion. And I was in high school by '81, so I probably would've remembered if we were still having problems.

Danya Gerasimova:

A lot of the folks that I spoke with link various health issues to cement factory emissions exposure— respiratory issues, higher rates of cancer. If you are comfortable sharing, is there anything that folks in your family link to impact from the factory?

Betsy May:

No, I don't think so. Our nextdoor neighbor had bladder cancer, but no one else around us died of cancer that I can remember.

Darrell May:

Mardell Schulte died of cancer. I don't know what it was or what contributed to it.

Danya Gerasimova:

Do you know about the CertainTeed asbestos factory that was right next to the Missouri Portland Cement factory?

Darrell May:

Yep. Is it still there? There was always a lot of talk that the whole [Maline] Creek is lined with asbestos from years and years of CertainTeed dumping their trash into the creek. I don't know whether that's true or not. I never went down there and dug around to find out.

Betsy May:

I was down there one time with Kathy Scott when I shouldn't have been. There were a few of us, and we walked down the railroad tracks, and there were people in white hazmat suits around there. I didn't know what they were at the time. We walked all the way over to Bellefontaine Cemetery, and I got in trouble when I got home because I brought back flowers from the cemetery.

Danya Gerasimova:

What year would that have been?

Betsy May:

I might've been 12. So '76 -ish? That's the only time I ever went anywhere near there. I got talked into it because all the other kids were going.

Danya Gerasimova:

Was CertainTeed something people talked about in conjunction with the Missouri Portland Cement factory in the '70s? Or was it something that you only became aware of later?

Darrell May:

They were kind of separate issues.

Betsy May:

I don't think I ever heard of them until after I was an adult. There was something in the Riverfront Times about it. Until then, I didn't know that was a problem.

Danya Gerasimova:

Did CertainTeed or other factories in the vicinity have visible smokestacks, or was Missouri Portland Cement factory’s the only one visible?

Darrell May:

It was by far the largest. Whether the others had them or not, they were probably just metal vent pipes coming out of the buildings or something. Nothing that would really catch your eye.

They might've been just as bad or worse; I don't know. But they weren’t huge structures sticking up in the air.

Danya Gerasimova:

Can you tell me a little bit about the neighborhood in the '80s and '90s?

Darrell May:

Like I said, the majority of people that bought houses when they were newly built stayed until they couldn't stay any longer. And for a long time, no houses in our neighborhood and in Bellefontaine Neighbors in general went on the market. The people stayed in them. And if they changed hands, it was usually the kids buying them from their parents.

For a long time, Bellefontaine Neighbors did not allow "For sale" signs in the yards of houses. It was a city ordinance. So somebody from out of town couldn't drive through there and say, "Oh, there's a house for sale." It was word of mouth.

Then, a big realtor firm sued Bellefontaine Neighbors and won, so they were allowed to put signs in the yards. I think that was in the early '80s. So that family neighborhood started breaking down in the '80s and '90s. At that point, there were outsiders. We were outsiders ourselves when we moved in.

The second generation started leaving. They didn't buy mom and dad's house and stay there. Instead, they went to St. Charles. And that happened all over North County. That wasn't just Bellefontaine Neighbors. As I recall, the original people stayed as long as they could, until the late '80s and the '90s, just because of the age they were getting. The kids moved out to St. Charles or St. Peters, and mom and dad got old enough that they needed to go somewhere. So they moved out by the kids.

Betsy May:

The real problem was loss of industry, churches, and schools that anchored the community.

From about 1950 to 2000, most of the people living there were either WWII veterans who got married and raised a family, or the children of those people. As those older homeowners passed away or moved to be closer to their children, there were a lot of 50 year old un-updated homes that went on the market all at the same time. Unlike the buyers of the previous generation who bought and lived out their entire lives in these homes, the new buyers were interested in affordable starter homes. Many homes were turned into rentals. They were not anchored in the community the way the previous generation was.

North County in general was an aging blue collar community at that time and lost a lot of jobs due to plant closures and layoffs. In addition to Portland Cement, the Ford plant in Hazelwood closed; the GM plant moved to Wentzville, and McDonald Douglas laid off a lot of the machinists. Those jobs were anchor jobs for the North County community.

And then the school district, Riverview Gardens, was losing accreditation around 2001 or 2002. My daughter was entering junior high. We were in Glasgow Village at that time, about a mile and a half from mom and dad's house. So we had to decide whether or not we wanted to send her to private school and stay where we were or move to a different school district. We wanted her to go to another school district where she could graduate with a diploma, so that was the reason that we left. I think people look at school districts when they make their decisions about where they want to live.

Around 2004, Cardinal Raymond Burke came to St. Louis. The St. Louis Catholic Archdiocese decided to consolidate Catholic perishes. That contributed to the loss of community as well as the neighborhood churches and schools shutting down. All of this happened at about the same time.

Cindy May:

There were about six families that we were close to. And like I said, we were the young ones. Harry died, and Deanie had to stay there by herself. Within a couple of months, the man across the street died, and the other neighbors moved out with their kids. It was like they all moved at one time, and then we moved within two months at the end of 2002. And not on purpose. It just happened once [Darrell] had retired.

Darrell May:

We bought a house over here in Illinois, and we moved around Christmas time between 2002 and 2003, right in those two or three weeks. We didn't plan it, but everything just fell in line.

Danya Gerasimova:

Have you paid any attention to the factory and the quarry in the '80s, '90s, and 2000s? Betsy, you mentioned your brother used to play there.

Darrell May:

We don't know how much, but I think he and his gang did. He was a skateboarder back in that era.

Danya Gerasimova:

Was that in the '80s?

Cindy May:

Yes. And that was before the skateboard. I asked him about that.

Darrell May:

You get a bunch of boys; they're going to find a place to make trouble. I don't know if they were making trouble, but they just were where they weren't supposed to be.

Betsy May:

I worked for the P.D. George Company down on Hall Street in the '90s. A coworker was driving home from work one day, and there was a tornado, and it picked up something from the cement plant. I want to say it was one of the cement mixers from the back of a cement truck. It came over the fence, and it landed on top of her car. It totaled her car, but she was not injured. She was very lucky.

Cindy May:

I remember that. It rolled down the hill.

Danya Gerasimova:

Are you guys familiar with Cementland?

Darrell May:

We were aware that it was happening, but we were gone from the area by then. I think we heard of it on the news, on TV. We lost contact with everything over there when we moved. But we'd go down Riverview Dr and see them pushing dirt around, and all of the cement barrels being set up on top of the ridge there.

Cindy May:

We've seen [Concrete Jungle Gym,] the program on PBS. It's just wonderful.

Betsy May:

I think a lot of people were excited that it was going to be something other than just an empty abandoned lot. They had seen City Museum and what he had done down there, and it was exciting to think what he could do here.

Cindy May:

Are they still planning on doing anything with it?

Danya Gerasimova:

It doesn't seem like it. In 2022, a trucking company bought it. And it's unclear what they're going to do with it, because demolishing those buildings seems very costly.

Darrell May:

Yeah, I'm sure it would be. And it'll probably turn into a Superfund site for the pollution people. I mean, it's got to be nasty.

Cindy May:

I was talking to my friend Phyllis Paro, and she told me that there was graffiti all over it now.

Danya Gerasimova:

Yeah, that’s true. What sort of impact do you think Cementland would’ve had on the neighborhood had it been opened to the public?

Cindy May:

Wonderful.

Betsy May:

I think it could have kept some of those stores open down at the Riverview Plaza, and people would have wanted to live close to work. It could have had a positive impact.

Darrell May:

I don't know. It would've been a tourist attraction, but the neighborhood we lived in was far enough away from it that it wouldn't have made a whole lot of difference. I don't think it would've brought in any business to speak of. I think people would come in from Riverview Dr and leave on Riverview Dr, and they wouldn't hang around.

Danya Gerasimova:

If it was up to you, how would you like to see that huge factory space used to benefit the community?

Darrell May:

It's pretty large and it has railroad facilities, and it has potential for port facilities on the river. It could have created jobs for people to live in that area depending on what went in there, but nothing has ever happened. The way the property was left with all those old industrial structures, it would be expensive to redo.

Danya Gerasimova:

Thank you so much for your time, and thank you for sharing your archive [of documents related to the Missouri Portland Cement factory], Cindy. Have you been keeping this folder since 1972?

Cindy:

Yes.

Betsy May:

I told her she better share it with you because nobody else is going to understand what it is.

Danya Gerasimova:

Why did you decide to keep these documents?

Cindy May:

I keep everything.

Betsy May:

She keeps track of all kinds of stuff. She writes stories down. When my daughter was born, she wrote a story about sitting in the hospital waiting to see her come out, not knowing whether she was a boy or a girl. So she has a habit of writing things down.

Danya Gerasimova:

Have you ever published anything?

Cindy May:

No. Heavens no.