Interview with Michael Allen about Lafayette Square, 2025

NO ALTERATION

05.02.25

Phonecall

%20Large.jpeg)

Michael Allen is a Professor of History at West Virginia University who served as the Executive Director of the National Building Arts Center in Sauget, Illinois, from 2022 to 2024.

Danya:

Can you tell us about the Lafayette Square neighborhood prior to the 1970s?

Michael Allen:

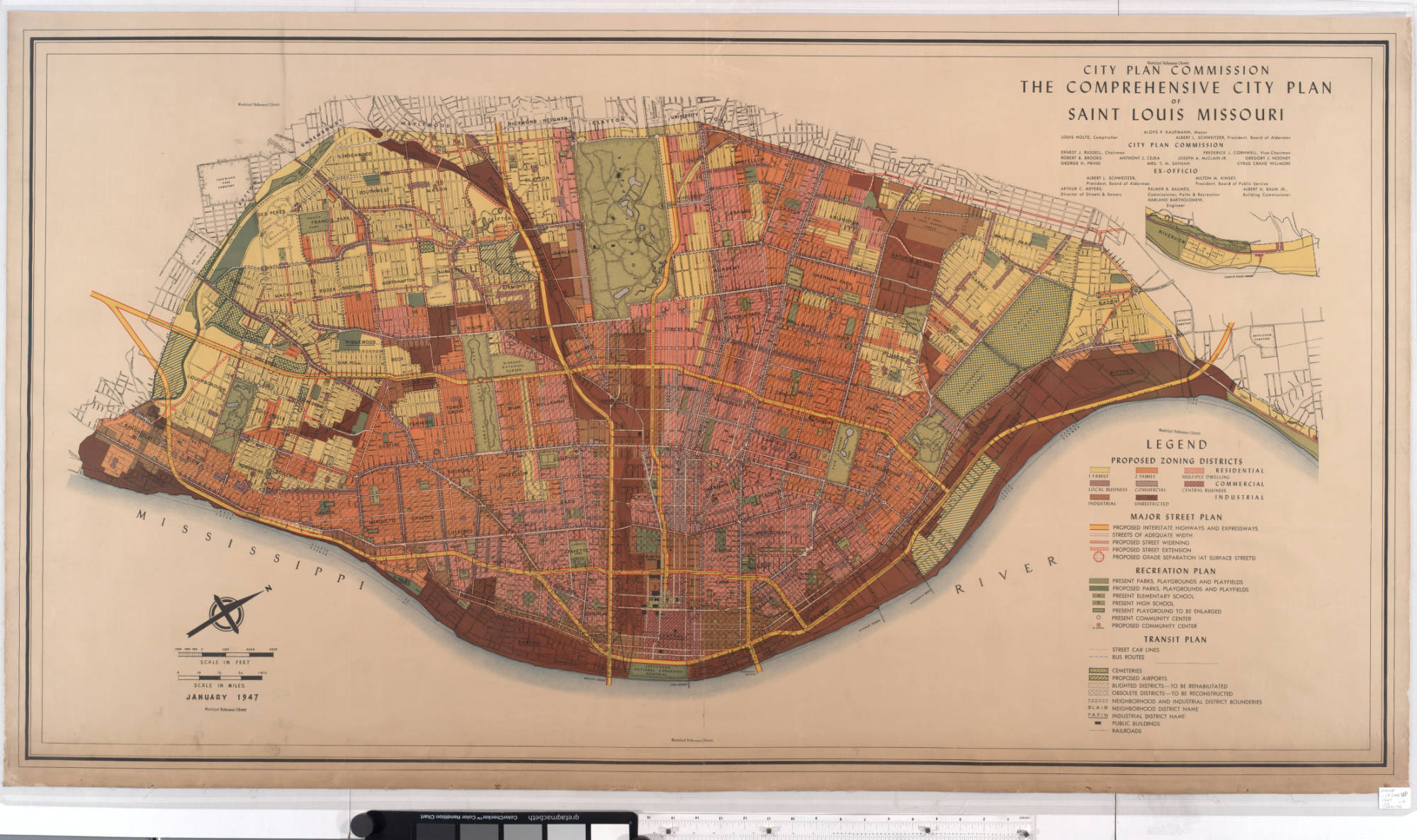

Lafayette Square is interesting in the city's history because today it's so gentrified and looks so good, so complete, that few would remember or even think about its past. To me, a crucial bit of the pre-1970 history is the 1947 City Comprehensive Plan, which called for the total clearance of Lafayette Square. The City Plan Commission had decided it's substandard and all the housing needs to go, and there were blueprints of how to tear it down and rebuild it as a low density cul-de-sac suburban, kind of garden city area.

And that rising resentment led a very eccentric architect and historian named John Albury Bryan into the neighborhood. In 1949, he purchased 21 Benton Place and fully restored it back to its 1870 condition. He'd walk around the neighborhood in a top hat and coat, very much setting the stage for the romanticization of its architecture and calling out the fact that this great collection of buildings could be lost forever. Photographs of his restored parlors appeared in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1956 and helped inspire interest in preserving the neighborhood.

The city eventually designated Lafayette Square as its first local historic district in 1972, and the area around the park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places that same year. A lot of the rest of the neighborhood was listed in the National Register later, in 1986. So it's a real turnaround in terms of creating rules and laws to protect the buildings. Albury Bryan and his impulse led to more interest in the preservation community. And the preservation has popularized the area as a cheap alternative to other parts of the city, where you could literally buy a mansion for a song instead of a row house. It gained a reputation as a place where people of very modest means, but who wanted to put the hard work in, could live in even bigger, grander houses than in Soulard or Benton Park.

Some people went to Soulard attracted to its density and the taverns on every corner. Soulard definitely had more of the neighborhood feel, but Lafayette Square had this architectural grandeur and this Victorian square. There's some magnetism that either pulls somebody to Lafayette Square or Soulard. In our larger narrative, I don't know what it means that Bob Cassilly went to Lafayette Square and Larry Giles went to Soulard. I would surmise that Lafayette Square is more about spectacle and texture, vibrant colors, ornate buildings, and Soulard is more austere and communal, more working class. I think their choice of homes in this rehab era is very much indicative of how they envisioned preservation. To Cassilly, it was this exuberant, larger than life project, and to Larry, it's just a very careful endeavor that brings ordinary people together, and it's much more modest and controlled.

Lafayette Square certainly attracted a lot of people interested in the arts, but also a lot of politicians and aspiring politicians. After all, it's literally a place where the Gilded Age rulers of the city lived. So if you envision yourself as following in their footsteps, and someday you want to be the alderman or the mayor, you buy a burned out shell of one of the mansions of the Gilded Age elites and fix it up. And someday, you'll be in that position and have the house to match.

Danya:

And the 1947 Plan included a highway getting built by Lafayette Square, right?

Michael Allen:

Yeah.

Danya:

So it used to be this elite neighborhood with mansions in the late 1800s. At what point did it fall into disrepair?

Michael Allen:

A lot of people talk about the Great Cyclone in 1896, but I think that comes a little bit later. I think it's a nice historical benchmark for its decline. It was literally not the same after 1896, but a lot of the wealthy families were abandoning Lafayette Square as early as the 1880s for Compton Heights, where they could have even larger houses. I think what was important to them was the larger lots, more separation, more privacy. In Lafayette Square, the bigger houses are pretty close together. You can see your neighbor's activities in their yard from your window. So they were moving to sites where their lots were five times wider and deeper. They were going to Central West End and to the private streets that opened. Westmoreland and Portland Places opened in 1888. And unlike Lafayette Square, you're not sharing space there. The rich aren't even running into each other. They go to their carriage step, and they get picked up by the driver. It's the world of elites: seclusion.

And Lafayette Square, even in its fine days, had shoe factories and plain mills built on its edges. With Interstate 44 now cutting through there, people don't remember that at the peak of the wealthy heyday of Lafayette Square, it would've been integrated into the neighborhood to the south. Which meant that your mansion is just a few blocks from common workers, and there are no gates to keep them out. So it's not as controlled and secluded of a place. And also because of that, the display of wealth through these big mansions was way more visible. Ordinary people were walking these streets, and seeing these mansions, and knowing who lived in them. So what a way to maintain social dominance when they started moving to Central West End and eventually out to places like Ladue. They move to places where ordinary people aren't even allowed to walk down the sidewalk.

But in Lafayette Square, they were on full display. It's very European in that manner, like an old European capital city, like London or Brussels. It's not architecture designed for the kind of freewheeling, bohemian culture that would take root there in the 70s, that's for sure.

Danya:

As those wealthier residents were moving out, did more middle class or working class folks move into the neighborhood, or was it just abandoned for a while?

Michael Allen:

I think there was a gradual transition. A common narrative is that people start leaving, and houses are turned into boarding houses. And that is true; people did chop up these mansions and townhouses and make apartments. Although in some cases, they were simply just sold to families of less wealth, and then they sold them to families of even less wealth. And by the 1940s, when the city planning commission was calling for demolition, most of these buildings had severe deferred maintenance. They were in really rough condition. And a lot of them were built in the era before indoor plumbing. So even when the wealthy were living there, their water would've been brought in by servants. Many of them had been adapted, but they were not designed with modern plumbing systems. So they weren't luxurious. They would have needed a lot of upgrades to keep the rich in the first place, and the wealthy could just build another house, and the new house could have indoor plumbing from the beginning.

So there's a transition between the 1880s and the 1920s. And by the 1920s, it's a faded landscape. But if you look at photos from that period, it doesn't have the obvious signs of decay and decline that it would develop right after World War II. By the 1950s, you're starting to see broken windows. And by the 1960s, you start to see buildings that are dilapidated, including collapsed roofs, just shells. And demolition is a factor in the 1960s and 1970s in the neighborhood. And then you start getting these gaps, these empty lots in the neighborhood between the houses. So not the most hopeful looking place by the 70s.

But again, where else could you get something from the Victorian age that beautiful for a hundred dollars? Soulard, LaSalle Park, and Benton Park stayed a lot more intact. And so when rehabbers moved in there, many buildings were worn down but still occupied. And Lafayette Square was a place where a lot of these buildings were vacant or literally just abandoned, not habitable at all. So it's a bit of a different story in terms of the transition and how much harder it was to turn Lafayette Square around than Soulard. And Soulard still had neighborhood bars, neighborhood hardware stores, a bank, and the Soulard Market. Lafayette Square was ghostly.

Danya:

Could you talk more about the demolition plan and the context of city planning around it?

Michael Allen:

The 1947 plan was the first comprehensive plan for the city that was written by city staff. So it's a hallmark of professional city management. The city had adopted a plan written by an outside organization in 1907, so it was 40 years later. Automobiles hadn’t been an issue then, but they were in 1947. So the city was really worried about not being adapted to this new transportation technology. Also by 1947, it's not even a guess that the suburbs are going to be the biggest threat to the city's near term survival. They're booming. And so the 1947 plan is an attempt to rationalize the zoning code, to streamline city freeways and auto access, and to eliminate once and for all the historic "slum neighborhoods" around downtown St. Louis: the oldest neighborhoods including Lafayette Square and Soulard, as well as Old North Hyde Park, JeffVanderLou, and St. Louis Place. It's a big swath that would've been taken out. And in the plan, they were declared obsolete beyond repair, not even worthy of a heritage designation as a historic artifact. They are just substandard, unsanitary, and dragging down the tax base because more profitable real estate could be there.

And in 1949, the federal government passed the US Housing Act, which created the first federal money for slum clearance, direct expenditures to cities. So the city plan in 1947 was on the precipice of that money. A lot of cities were planning in that period, because they knew the money was coming; they knew that Congress had been debating this law as early as 1945, right at the end of World War II. So St. Louis is trying to coordinate, because they're like, "We've got a big job to do, and the only way it's going to succeed is if we get federal money." There's no way the city can afford to do any of this hard work.

There's an Architectural Forum article from 1951 that declares St. Louis's plan and its implementation to be "slum surgery," using a medical reference, almost like it's removing cancer from the body of the city. And there were very few voices of protest. John Albury Bryan was really the first person who said, "Wait a minute. We might be throwing out something that has cultural and architectural value."

1949, the year he moved into the neighborhood, was also a turning point because it was the year Congress chartered the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It would be another 17 years before there's a federal preservation law, but now, all of a sudden, there was a national organization entrusted to go out and purchase valuable historic properties and save them from demolition. So we have two trajectories that are going to collide: tearing old parts of cities down and this new attitude that maybe there's something valuable that should be preserved, that urban renewal could be something people driven and building focused, rather than clear cutting with infrastructural projects and bulldozers.

In essence, the kind of person who would see Lafayette Square differently than the official city government document would probably have to be somebody who sees the world differently, somebody who's just a little countercultural. Or a lot.

Danya:

So how come Lafayette square wasn't demolished, whereas JeffVanderLou and other neighborhoods were?

Michael Allen:

That's a great question. There's a simple answer about race and the Delmar Divide. I think when you look at Soulard versus Old North, or McKinley Heights versus JeffVanderLou, the racial redlining can be factored in. The areas on the south side that were supposed to be demolished are still there. And on the north side, they're not. And I think that's because banks weren’t giving capital to the majority African American areas. Lafayette Square was a really hard and really expensive place to redevelop, and I think it did benefit from being on the south side of that racial red line.

There's a more complicated answer. One of the reasons Lafayette Square was in a strong position is the concentration of really picturesque architecture. St. Louis Place has a little bit of that too, and a lot of that has survived on St. Louis Avenue around The Griot Museum. So I think there's a social kind of energy that preservationists encourage. The biggest and grandest buildings are special, and I think Lafayette Square benefited from that, whereas it's a lot harder to make the case for average buildings.

Lafayette Square was almost cheek by jowl with public housing projects to the east and the City Hospital, so it was not really a bastion of whiteness at the time either. It was in a very integrated part of the city. That would change, and that's a discussion to have too. But I really just think the bias towards ornate and more grandiose architecture was on its side.

Another thing to note is that the area around Ralston Purina in LaSalle Park that used to be called Frenchtown had some of the oldest row housing in the city that would today remind people of Baltimore, Philadelphia. Most of that got demolished, even though it was older and potentially more of a priority than Soulard. But it was all working class, extremely narrow tenement flats—and that area got mowed down. And I think that bias in architectural preservation is one of the reasons. Because that's on the south side, so you can't really ascribe that to red lining.

Danya:

And those Southside neighborhoods, Soulard and Lafayette Square itself, were primarily white neighborhoods by mid-century, right?

Michael Allen:

They really didn't integrate. Soulard definitely not. That might be another factor.

Liz:

Were housing covenants in place in that neighborhood at the time as well?

Michael Allen:

Some covenants would have existed in Lafayette Square, but attached to individual properties. By the time the covenant system was created through neighborhood associations after 1910, the neighborhood was already pretty much abandoned by the super rich. So it never got the block by block covenants that popped up all over the areas west of Jefferson Avenue.

Danya:

So who were the rehabbers moving to Lafayette Square in the 1970s? And where were they coming from?

Michael Allen:

I think some of the people making up the movement were architects, some artists. There were a lot of young professionals involved: accountants, bankers. So there were generally two ends: one is the creatives who are going to mostly do their own work. And then there's the upwardly mobile young professionals who are looking for an alternative to the tedium of the suburbs. They're not going to live in any of the suburbs, and they are also really bored by the more stable neighborhoods like the Tower Grove area with their old church going populations. They want to be around other exciting young people. They want to live in cool housing. They want to do something completely different, and they don't want to live in the suburbs.

I think a lot of these people, from my knowledge, are native St. Louisans. A lot of them, including Bob Cassilly, grew up in the suburbs, so they know that's not what they are looking for. And Lafayette Square is one of those destinations to try to live a little differently. It's still St. Louis, but maybe it could be hip and fun and cosmopolitan, and they were getting to remake the neighborhood. So it's this completely creative process. It's not buying a house for your nuclear family; it’s buying a house that you might live in with a bucket for a toilet and a back wall of plywood.

I think there's an element of adventure to it that attracts a lot of people. But again, a lot of these people have affluent backgrounds, so it's not a risk. These aren't poor people fixing the houses up. These are people who have the means that are going to protect them if they fail. I think that's where the gentrification story is inseparable from Lafayette Square's narrative. I'm not saying that to attack anyone. It's just that these are people who have access to money. That means they can A, afford to do this, and B, not going to be devastated financially if things don't quite work out. And it's mostly white people too. There are some African Americans, but it is not mirroring the racial demographics of the city. It's whiter. It's not too different from other Southside rehab neighborhoods, but it stands out to me given there are Black professionals with money in this period, but they're not there.

Danya:

So do you see it as gentrification affecting the residents of Lafayette Square who lived there prior to the 1970s?

Michael Allen:

I think it's definitely like that. It's a touchy subject with the old timers, because they don't want to be associated with gentrification. And a lot of them would probably say, "I bought a house that needed a million dollars worth of work, and I was making $20,000 a year in the 70s. So I'm not rich." But they were able to get bank loans, and have credit, and have access to resources. Other people didn’t. And a lot of other middle class people didn’t have the resources to take on that big of a house with that expensive of a price tag.

Were they living paycheck to paycheck? Were they maybe going broke rehabbing these old houses? Definitely. But in the end, are they selling these houses for huge sums? Yes. And there's a discourse about rehabbers that is very much in the language of western pioneers, settlers, the West, enterprise. It's like, “You do the work, but you're going to end up reaping the financial reward.” And I know some old timers who are still in the neighborhood, who have not sold their houses. Maybe that's not their game plan, but the improved value definitely is. In American capitalism, that's a factor.

So Lafayette Square residents were really into this DIY aspect, but a lot of people couldn’t do it themselves because of their background. And there wasn’t any effort to bring people into the neighborhood who might need assistance or financial help. There was no effort to diversify who's there. So in that way, the Lafayette Square story really mirrors a pretty typical gentrification pattern.

And it’s also like what was happening at Greenwich Village with Jane Jacobs. These people who go to city planners and leaders and politicians are still pretty radical. They want to save these old houses and save this neighborhood. But then you look at the neighbors over in the public housing project half a mile east of Lafayette Square, and they're like, "We don't even know who these people are. They never come over and talk to us." And eventually, the Lafayette Square residents succeeded in removing the basketball court in Lafayette Square in 1997, which was the number one destination for young African American teenagers in the housing projects at Darst-Webbe and Clinton-Peabody. So it's very unneighborly.

.jpg)

Danya:

So the gentrification of Lafayette Square really affected those neighboring areas?

Michael Allen:

I think there were two major impacts on surrounding areas. One is to the west, in an area between Jefferson and Grand and between Chouteau and Highway 44, variously called Compton Hill or Eads Park—kind of a set of neighborhoods. But it was historically more African American. Some areas were more integrated, some areas Black, like Compton Hill proper. Well, Lafayette Square residents pushed Mayor Schoemehl in the early 80s to adopt a redevelopment plan for that area that relied on a lot of demolition and reconstruction. The Lafayette Square residents were obsessed with old buildings in their neighborhood, but for this area, which is mostly Black and not well off, they wanted to tear it down and build fake Victorian new urbanist houses, which is a lot of what you see west of Lafayette. It's like, well, that might be good for your property values, but that's not preservation anymore. So that's one impact. And then to the east, the Lafayette Square residents were a big part of the coalition that pushed the plan to tear down the public housing at Darst-Webbe in the 90s that led to a net loss of hundreds of public housing families.

On the other hand, Lafayette Square residents were also the loudest voice to keep the old City Hospital across from the Walgreens there on Lafayette from being demolished. That's a public hospital for poor people that was almost demolished. So it's strange. They are very selective in terms of historic preservation, which is supposed to be their goal. It's not consistent, and it's not consistent when there are poor and Black people involved. And neighborhood residents don't want to hear that.

Also, in 1984, Lafayette Square elected a white alderwoman, Marit Clark. She unseated an African American politician who lived in the public housing. And while her campaign is not openly racist, it's based on a “get out the white vote” strategy. It was very questionable in terms of the values of egalitarianism. And when Marit Clark became alderwoman, she wanted the hospital torn down, she wanted the public housing torn down, and she didn’t really build a coalition with the Black neighborhoods around Lafayette Square. Is that because a lot of the Lafayette Square people saw themselves as reformers who want change, and the African American political machine in that area was tied to the Lebanese political machine, so it was seen as corrupt old school politics? I don't know. That's kind of an age-old divide in urban politics, but all I know is there wasn't a sense at all that everybody is going to rise together.